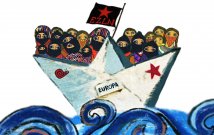

The exchange between the Zapatistas and movements and communities in Dublin “from below and to the left”

And why they came.

MA in Community Education, Equality and Social Activism at the National University of Ireland Maynooth

The exchange between the Zapatistas and movements and communities in Dublin “from below and to the left”

And why they came.

The Zapatista tour of Ireland is starting THIS WEEK!

Schedule and updates on Twitter and Facebook but basically West, South, East, North. It's conversations with movements and communities in struggle "from below and to the left" - so not really public events or awareness-raising. As they've always said, the best thing we can do to support them is to fight our own battles where we are - and that's what the tour is about.

Donations of any size are VERY welcome - link here.

I've written a pamphlet supporting the tour for a series edited by John Holloway and Ines Durasnita, with artwork by the amazing Kate O'Shea - you can download it free here.

Let's hope this is the start of a "hot autumn" for Irish movements...

From the Irish Heretics to the Zapatista Delegation on La Montana

From the fields, bogs, ditches, alleyways, roads, boreens, woodlands, valleys, beaches, rocks, stones and city streets of Ireland we would like to welcome you our Zapatista sisters, brothers and others to our little island on the edge of Europe, this continent you are now ready to land upon.

We welcome you as we welcome people from all places from across the world in all their diversity who come to our shores.

We are an island and a place apart, with our own language, culture, music and history. We are part of Europe but our story and the story of Europe are not the same story, and our memory of empire and Europe’s memory of empire are different memories.

We know that Europe is a place of the colonisers because our island too was a colony of one of the European empires, and the struggle for autonomy and independence left a deep scar in the form of an invisible line that they call a border, and so made our single island into two territories*, and again showed that empires are masters of division and separation.

That struggle for freedom was the product of many years of people working together, fighting to take back the land, resisting and rebelling against an occupation of place and of mind. For many on our island that struggle continues.

We know too now though that Ireland is in the grip of another empire, that we now live in a place where the forces of neoliberal globalisation find a comfortable home, and that much of our work now is to decolonize the minds of our people from the politics of heteronormative capitalism and liberate Ireland from this new empire without borders which dominates all aspects of our lives.

We are people from below and to the left, doing what we can in our own ways, in our cities, towns, and fields to build alternatives while we resist the omnipresent and seemingly omnipotent forces of capitalism which in our society have become so normalised that to attack them seems like heresy.

So we are the heretics of Ireland, calling our sisters, brothers and others Zapatistas. Come and see us as we would love to talk and exchange with you all, to see how our struggles can nurture one another as we nurture the land around us, and how we can plant seeds today so the rebels of the future can have a bountiful harvest.

* For the purposes of sailing and seafaring we are still just one island, in case you want to come to visit us by boat.

De lxs herejes irlandeses a la delegación Zapatista de La Montaña

Desde los campos, pantanos, barrancos, callejones, caminos, senderos, bosques, valles, playas, rocas, piedras y calles de las ciudades de Irlanda queremos darles la bienvenida a nuestroas hermanas, hermanos y otroas Zapatistas a nuestra pequeña isla en la orilla de Europa, este continente en el que están listoas para aterrizar.

Les damos la bienvenida, como damos la bienvenida a las personas de todos los lugares del mundo, en toda su diversidad, que llegan a nuestras costas.

Somos una isla y un lugar aparte, con nuestra propia idioma, cultura, música e historia. Formamos parte de Europa, pero nuestra historia y la de Europa no son la misma, y nuestra memoria del imperio y la de Europa son memorias diferentes.

Sabemos que Europa es un lugar de colonizadores porque también nuestra isla fue colonia de uno de los imperios europeos. La lucha por la autonomía y la independencia dejó una profunda cicatriz en forma de una línea invisible, que llaman frontera. Y así se convirtió nuestra única isla en dos territorios*, y demostró de nuevo que los imperios son maestros de la división y la separación.

Aquella lucha por la libertad fue el producto de muchos años de trabajo conjunto de la gente, luchando por recuperar la tierra, resistiendo y rebelándose contra una ocupación del territorio y de la mente. Para muchxs en nuestra isla esa lucha continúa.

Sin embargo, ahora también sabemos que Irlanda se encuentra entre las garras de otro imperio: que ahora vivimos en un lugar donde las fuerzas de la globalización neoliberal encuentran un hogar cómodo. Sabemos que gran parte de nuestro trabajo ahora se encuentra en descolonizar las mentes de nuestrx pueblx de las políticas del capitalismo heteronormado y liberar a Irlanda de este nuevo imperio sin fronteras que domina todos los aspectos de nuestras vidas.

Somos gente de abajo y de la izquierda, haciendo lo que podemos a nuestra manera, en nuestras ciudades, pueblos y campos para construir alternativas mientras resistimos a las omnipresentes y, aparentemente, omnipotentes fuerzas del capitalismo que en nuestra sociedad se han normalizado tanto que atacarlas parece una herejía.

Así que somos lxs herejes de Irlanda, llamando a nuestras hermanas, hermanos y otroas Zapatistas. Ven a vernos porque nos encantaría hablar e intercambiar con todoas Ustedes, para ver cómo nuestras luchas pueden nutrirse mutuamente como nutrimos la tierra que nos rodea, y cómo podemos plantar semillas hoy para que haya una cosecha abundante para lxs rebeldes del presente y futuro.

* Por los efectos de navegación y marinería seguimos siendo una sola isla, por si quieren venir a visitarnos en barco.

People interested in helping out with the Zapatista visit to Ireland:

Please contact zapsgoheirinn AT riseup.net

How do we make sense of different kinds of Irish government today? There is a "crisis" in Irish politics that fundamentally consists of a long-term shift to the left, driven by large-scale mobilisation in the water charges struggle, the marriage equality and abortion rights referenda, and other anti-austerity struggles. It has become (tiny violins) difficult to put powerful right-wing governments together - as elsewhere on the European periphery, there are no longer social majorities for the politics of austerity and neoliberalism. But the twilight of liberalism is lasting a long time.

I published this in the late, lamented Irish Left Review back in 2016 just before the general election. You can still find the original here but it is becoming harder to do, so I thought it worth rescuing - not quite for posterity but just for myself.

Back then the question was whether a stable majority could be reached post-election. Now, in December 2020, we have what this piece called "a complex coalition", in which two days of (fairly intense) pressure (12 - 14 Dec) forced the Green Party to get the ratification of the EU's free trade agreement with Canada (CETA) taken off the order of business. That does not of course mean that it has gone away - but it does illustrate the basic point that in neoliberal contexts, a "weak government" is often a good thing for social movements.

--

With the general election now upon us, Fine Gael and Labour can be expected to highlight the need for a “strong government”, while attacks on the left parties have suggested that they are uninterested in governing and only interested in being “wreckers”. This can be a difficult argument on the doorsteps, against a long history of assuming that only parties in power can “deliver” (usually particular benefits for local groups). I want to suggest that ungovernability would not be such a bad thing, and that a “weak government” is in the interests of most people in the country.

What “strength” has meant over the past five years has been strength at imposing decisions made elsewhere – by the Troika collectively, by the EU or ECB individually, by “the markets” or in some sweetheart deal with multinationals – on a population which has been increasingly recalcitrant. Not strength in representing our interests, but strength in riding roughshod over our interests and our resistance. A strong government is not our friend if it is on the right (and there is no real chance of anything else in the next Dáil).

Conversely, on all recent opinion polls a weak right-wing government is almost certainly the least bad outcome we can hope for, whether that be a coalition of FG, Lab, SDs and independents or – on different numbers and backroom deals – FG in some sort of arrangement with FF (minority government? government of national unity?) The reason for this is that a weak government is one which is less cohesive, and less effective at imposing other people’s interests in the face of our resistance.

I don’t want to overstate the case for this – even a weak government will pull together and ignore all possible popular resistance to, for example, the US military use of Shannon or Shell’s presence in Erris, and will continue to stand over whatever violence is required. However, not every issue will be so easy to handle. Water charges stand at the head of the list of a series of impositions by recent “strong governments” which may prove far more politically problematic for a “weak government”.

At its simplest, a “weak government” is one which will have to pay far more attention to social movements and popular pressure; it will have fewer rewards to offer for loyalty and will have less scope to threaten internal “dissidents” within what is likely to be a fairly thin majority. Indeed, the strategy of “ram the changes through and people will have forgotten in five years’ time” becomes less likely if the government’s lifetime may be considerably shorter.

Readers will make their own assessments as to which particular assaults on the population will prove harder to push through in the case of a complex coalition, minority government or narrow majority, but it will almost certainly involve some elements of austerity, and probably some issues of civil liberties (with which recent governments have played fast and loose). As with marriage equality, so too with repealing the 8th amendment we may even see politicians racing to put themselves at the head of the parade in the hope of convincing voters that they, and not popular pressure for change, should be praised for taking action.

In a very general sense, then, social movements, community groups and trade unions have everything to gain from a “weak government” which will have to struggle for support to stay in power, and some of whose members or supporters may seek instead to find popular allies rather than undergo further meltdown while in power. Meltdown will not be a problem for Fine Gael, whose core voters genuinely seem to like what they are getting: but it would be a problem for Labour, the Greens, the Social Democrats or for that matter Fianna Fáil if they find themselves acting as junior partners in yet another austerity government where the “recovery” will be felt far less on the ground than rhetoric suggests – and where votes may continue to hemorrhage towards Sinn Féin, the left parties and left independents.

This broadly positions Ireland in a similar situation to Greece, Spain and Portugal, where popular majorities and consent for austerity politics have been hard to find for several years now. The European periphery is only governable at the cost of not looking under the hood at the degree of legitimacy of governments and policies: time after time we have seen parties elected on one mandate take a different tack once in power, referenda re-run when people have not voted the right way and in the case of Greece just how little real choice citizens are allowed. The case of Greece (and Portugal’s recent semi-coup by the outgoing president) also shows, of course, that peripheral states cannot by themselves overturn this state of affairs. If we want an end to austerity in Europe, our peripheral ungovernability will have to find strong allies within the core European states, whether parties or movements. But Ireland is now joining the rest of the periphery in refusing a social majority for austerity, and that is a step in the right direction.

So I want to suggest that we should be happy to be (relatively) ungovernable for now, and that we should actively make the argument that in the absence of a possible government opposed to austerity and neoliberalism, our best option is a weak (and if possible fragile) pro-austerity government faced with determined anti-austerity parties. It is in this situation where strong popular movements will best be able to win victories and force concessions, and start to shift the initiative towards our side, and away from the IFIs, the EU and our own homegrown rich.

A propos of nothing very much other than the need to push back against the sea of grim and stupid that sometimes threatens to overwhelm us...

Six months back, people thinking about a radical future for Ireland asked participants to come up with visions of what their local community could be in a better world. I was just digging through old emails and thought this might be worth a share. It's not great utopian writing - there was, em, rather a lot going on in April 2020!

Fundamentally I wound up agreeing with Marx's critique of the “cookbooks of the future” – or rather feeling that there isn't that much interesting you can say about how free people might choose to organise themselves except for “differently”, and hopefully “reasonably well and creatively”.

And

having spent many years in alternative projects of one form or another, there

isn’t quite the same leap of joy at the thought of more self-organised activity

any more – it is just life, minus the unnecessarily stupid, selfish, aggressive and

badly-managed bits. But then there are quite a lot of those to lose, and they do make a difference...

Anyway, here you go. Comments (and livelier utopias) very welcome!

Laurence

--

What Dublin could be like in a better future, some time from now:

We don’t live our lives under the shadow of an enormous canopy of financial trading, IFIs, MNCs, shareholders, banks, CEOs, managers and all the rest of it… People own and run their workplaces together. It’s a big learning curve for a lot of people brought up in more top-down societies, but the “democratic natives” have been doing it since childhood, and have learned the skills to get on with each other’s very different ways of being and talking, skills, comfort zones etc.

In Dublin, owners, landlords and managers are now looked on with something of the same suspicion that beggars, addicts and the unemployed used to be met with. People take pride in workplaces that are genuinely “theirs” – and in finding ways of including both those who were previously excluded and those who are learning how to work with others as equals for the first time.

Part of what’s made this possible is a huge shift away from “bullshit jobs” and pointless industries. Averting climate breakdown meant directly confronting a series of powerful industries – fossil fuel, airlines, meat production in particular – and the broader drive to growth for its own sake. Farming, craft, art, education, science, health, travel and so on still happen but in radically different ways. Advertising, banking, accountancy, fossil fuels, much of construction and most of the car industry, and a million other activities … don’t.

Transport has become much more collective, and has slowed down again. A lot more energy goes into design and engineering, working out ways of doing things that aren’t massively destructive, and mining the debris of previous generations’ junk. Agribusiness has collapsed, while fishing and meat production have shrunk massively. A lot more food is produced locally, and much less processed food is eaten. Slowly, natural processes are taking back land that was once given over to monocultures or industrial uses; many communities have taken on turning brownfield sites into spaces for ecological rebirth.

Many people move through several different focusses in the course of their life – as some people always did: often something showy and high-energy as young people, something more geared towards immediate production and the everyday if they become parents, and something more reflective or creative in later life. There are still practical benefits, as well as other people’s respect, to be had from doing things well, but most people find their retirement from full-time activity is a lot less habit-bound and constrained.

States have mostly withered away, once sharp class divides no longer need to be policed. Most people spend a chunk of their time in meetings, helping to organise the bit of the world they’re most interested in – a neighbourhood, the postal system, their workplace, the Internet, their local port, nearby mountains – but people are firmly discouraged from spending too much time in administration. To the surprise only of a few, this way of running things is at least as effective as the old managerialism driven by people’s career aspirations and desire to say the right things to those above them.

A few people have decided to retreat into religious communities where everyone agrees to operate by the rules of a church, or play at being capitalists, or dress up as Proper States. So long as they don’t try and impose this on other people – and people are free to leave – others normally let them at it. If they go too far down the route of punishing unbelievers, running armies or letting people starve, neighbouring communities usually step in to disrupt the game.

Borders, passports and citizenship are now historical memories, as vague as the Iron Curtain for most people today, and in a world that is no longer structured by artificial scarcity race and ethnicity no longer provide the same grounds for attempts to exclude others from workplaces or social support. Learning how to live with difference has been a real challenge, and is seen as part of what makes a competent, mature adult. While much of the world has always been multilingual, people in countries like Ireland are learning how to add a bit of a few extra languages for different purposes, and not making too much of a big deal of it. There are still challenges of many kinds, but people no longer nod their heads along with anti-traveller or anti-immigrant racism.

Societies and communities look after people in a range of ways, without too much blame. Many people struggle through no fault of their own – traumatic experiences, disabilities, a workplace that collapsed – while others are dealing with things like alcoholism, the desire to tell other people what to do, or toxic masculinity. There isn’t as sharp a divide between social workers and family / neighbourhood care: the people who are helping an individual or a family talk to each other about what they’re finding works and doesn’t work.

Education is no longer about getting a Good Job, showing off how bright you are or telling people what they’re supposed to think. “Banking education”, in which teachers’ job is to deliver a curriculum to empty minds, has faded and teachers, parents and students together agree how to run a particular school. Educational debate has broadened from compulsory Irish and religious control of schools being the only issue - to a point where ordinary citizens happily chat about the differences between Waldorf and Sudbury schools, Freirean and critical strategies for education.

Exams have gone (except as elaborate versions of online quizzes for fun), and people are encouraged to take their own routes through education. There’s a lot more variety, now that technical education isn’t looked down on and nobody does subjects just because they have to: active outdoors education, craft and farming, play and politics all come to life. And most people are able to think and learn much more effectively, because most study has to start later in life.

Parenting and childcare have become much higher-status activities. There is a lot less rhetoric about loving children - and a lot more practical love for actual children. The big economic changes along with the greater focus on human needs rather than more abstract notions of money-making and formal power have helped feminists and LGBTQIA+ people shift gender relations and how people handle sexuality to much more adult forms. Sexual violence is now condemned in private as well as in public, and boys and men who are found to have engaged in it are looked down on by other men.

But the most important part of all this flowering is that it is about freeing up human beings. Capitalism and states, patriarchy and racism, ecological destruction and robotic institutions, constrain and deform human behaviour. Break these up – and the constellations of interests and ideologies that support them – and all you’re really doing is free human beings up to be creative in how they go about meeting their needs together. So how people do things in Dublin isn’t a particularly fixed way of doing things, and not the only one on the planet or even the island. Free societies geared around learning and creativity keep on changing, and different places decide to handle things in different ways – while being very interested in some of each other’s more dramatic experiments.

... of course, the gap between here and there is precisely social movements and popular struggle, the "independent historical action" of large numbers of human beings that is needed to break up all those things that get in the way of living together well. And that is a much bigger challenge altogether. Still, we can dream.